#and the quay and the history

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

.

#I know I'm really biased#but I really love my home city#it's just so pretty and there's old stone buildings#and little cobble alleyways with cafés tucked into#and the quay and the history#I know to an outsider that it probably is kinda rubbish#but I love it

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

On the Quay

Artist: David Octavius Hill (Scottish, 1802 - 1870)

Date: 1825

Medium: Oil on panel

Collection: National Galleries of Scotland, Edinburgh, Scotland

Description

Although best known today for his contribution to photography, David Octavius Hill was a genre and landscape painter. In this oil painting we glimpse Leith, which was Scotland's main port until the 19th century, and the official port of Edinburgh. Leith dealt in grain, flax, sugar, timber, iron, paper and whisky, the profits from which filled the Edinburgh coffers. The painting explores different kinds of light caused by the low sun, falling directly onto the buildings in the background and filtered through the ships' sails. Note the beggars in the foreground with the little animated wooden figures.

#painting#landscape#quay#oil on panel#scottish culture#leith#port#edinburgh#buildings#ship's sails#ships#wooden figures#beggars#male figures#female figures#costumes#wagon#architecture#storefront#cloudy horizon#scottish art#scottish history#david octavius hill#scottish painter#european art#19th century painting#national galleries of scotland

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

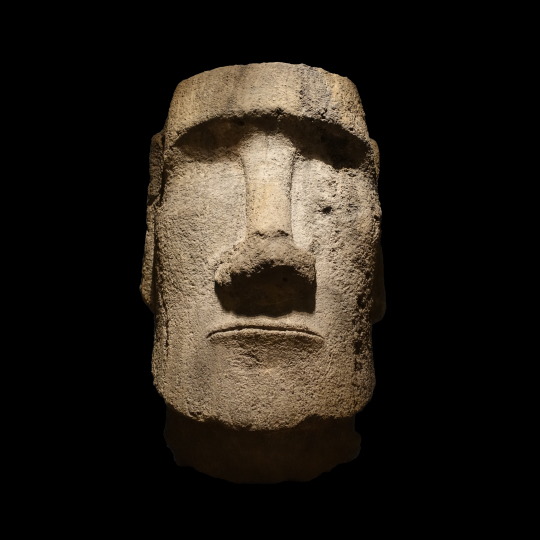

Moai Head, Chile, Between circa 1250 and circa 1500,

Basalt, H 170 cm (66.9 in) , W 100 cm (39.3 in), Thick 90 cm (35.4 in)

Collection Musée du Quai Branly, Paris.

#art#history#design#style#archeology#sculpture#antiquity#figure#moai#head#basalt#musée du quai branly#rapa nui#easter island

60 notes

·

View notes

Text

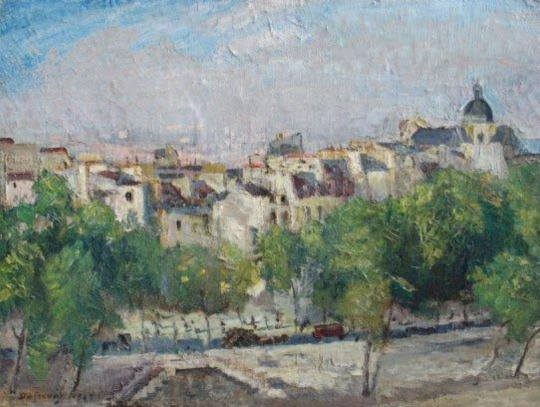

Georges Dufrenoy (1870 - 1943)

"Paris, Quai de l'hôtel de ville"

75 x 101 cm - Huile sur carton 1917

#dufrenoy#postimpressionism#art#georgesdufrenoy#artist#artistepeintre#artoftheday#artwork#painting#oilpainting#parismaville#hotel de ville#paysage#paysageurbain#urban landscape#landscapearchitecture#seine#quai#art history#artiste peintre#artists on tumblr#art collection#artiste#oil painting#paint#peinturealhuile#peintre#parisjetaime

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

pra mim isso aqui grita "eu sou uma pessoa rasa que quer se pagar de inteligente mas na realidade eu não dou a mínima nem pra arte, nem pra história, nem pro contexto em que a arte é posta e feita" tipo.... para de ser tão ignorante ou em primeiro lugar nem posta uma coisa dessas 🙃mas que coisa

#sim objetivamente todas elas tem uma diferença de detalhes gritante#mas você pelo menos se deu ao trabalho de entender o porquê que essas obras eram feitas em primeiro lugar?#quais eram os padrões colocados como ideais ou algo assim?#e além de tudo isso se você é letrado nesse assunto e mesmo assim tem essa opinião não tem problema até pq você tem um lugar de fala ne...#mas sendo uma pessoa X falando isso acho um pouco revoltante#bla bla bla#traditional art#art history#modern art#art critic

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

do you think ludinus has that crystal quay recorded or do you think he possibly got a hold of patia’s orb? those are the only two things I can think of that would’ve mentioned laerryn and lasted long enough to be found

Honestly I would be shocked if he had either. The orb seems like it would be the most likely candidate to earn a reappearance if one of the EXU Calamity artifacts were going to, but I doubt Ludinus would be the one to have it.

#and as much as i would like to see it#with the trajectory the hell's are taking right now#i doubt we're going to see anything which is fine#i'm also not sure i think quay's crystal made it out#i do like the idea of it from like... a historical angle#like and forgive me i'm paraphrasing but quay saying that history isn't really true because it's all about what people decide to make publi#so it's just a really good example of how unreliable history is if quay's story is the way her name gets into history books#but like this is also just the me obsessed with exu calamity talking#not what i realistically think would make it into a campaign#erin answers things#anonymous

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Maria de Macchi - Di quai soavi lacrime [Poliuto] - 1907

From Musical Courier 1909-01-20: Vol 58 Iss 3:

Maria de Macchi, Italy’s most famous dramatic soprano, died at Milan, Italy operation to remove a tumor. It January 13, from the effects of an was known the operation involved danger, but a fatal result was not expected. Her death is not only a blow to her friends and relatives, but a loss to the world of art. Maria de Macchi was forty-one years old. She leaves parents in Milan and a brother in New York City.

Maria de Macchi was engaged by Heinrich Conried early in his régime as the leading dramatic soprano of the Metropolitan Opera Company’s Italian wing. She came with the recommendation of many prominent singers. Her first appearance in New York was to have been made in “Gioconda,” but for a reason not revealed publicly the réle was given to Nordica exclusively. De Macchi sang first in “Lucrezia Borgia,” which, in spite of Caruso’s presence in the cast, was a failure. Her next rodle was Santusza in “Cavalleria Rusticana,” the second offering of a double bill. Only two critics were in the auditorium at the time. The others wrote slightingly of her performance. Her third appearance took place in “Aida” on a Saturday night. Again most of the critics were absent. Maria de Macchi went on tour with the Metropolitan Opera Company. Philip Hale, critic of the Boston Herald, gave high praise to her. Everywhere outside of New York she was received with acclaim. But disappointment at failure in this city was keen. Before she left America the soprano was taken ill, and her condition, with its fatal result, was traced directly to chagrin at the treatment she received here.

For several years Maria de Macchi assisted her brother, Celestino, in the management of his National Opera Company, which gives a season in Rome every Summer. De Macchi, who teaches singing in New York in the Winter, is related by marriage to Carl Schurz, Jr.

#classical music#opera#music history#bel canto#composer#classical composer#aria#classical studies#maestro#chest voice#Maria de Macchi#dramatic soprano#soprano#Golden Age Of Opera#Di quai soavi lacrime#Polito#Gaetano Donizetti#classical musician#classical musicians#classical history#history of music#historian of music#musician#musicians#diva#prima donna#La Scala#teatro alla scala#MET#Metropolitan Opera

1 note

·

View note

Text

Bordeaux

#france#bordeaux#city#les quais#waterfront#garonne#river#travel#history#photography#digital camera#plants#urban#gothic#neoclassic

1 note

·

View note

Text

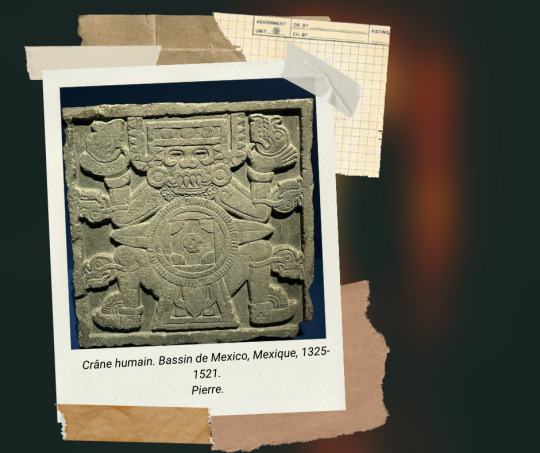

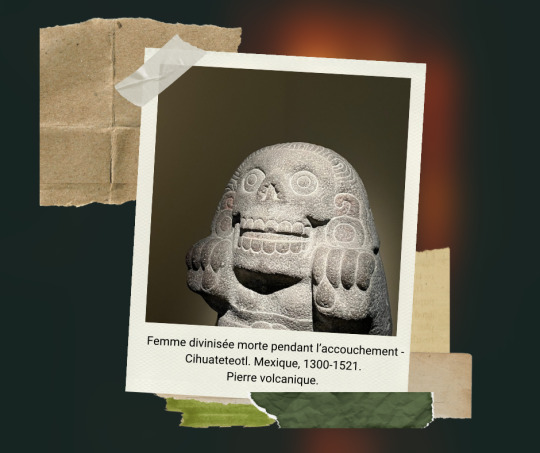

Mexica, les trésors du Templo Mayo dévoilés au Quai Branly !

Le musée du quai Branly - Jacques Chirac dévoile en ce moment une merveilleuse exposition retraçant l’histoire des Mexica (intitulée Mexica, des dons et des dieux au Templo Mayor). Ce peuple, installé connu sous le nom d’Azt��ques, est présenté sous un jour nouveau. C’est le terreaux fertile d’une découverte inédite la cité de Tenochtitlan, détruite par les colons espagnols. Grâce à un regard aiguisé construit avec près de cinquante années de recherches archéologiques sur cette histoire mésoaméricaine, l’exposition retrace les travaux focalisés sur la culture, l’art ou encore l’architecture de cette civilisation.

Ces recherches, effectuées par des professionnels passionnés, sont présentées dans un parcours dense et particulièrement riche. Organisée avec le concours de l’Institut national d’anthropologie et d’histoire de Mexico (INAH), l’exposition comporte plusieurs thématiques qui permettent d’envisager le peuple Mexica avec beaucoup de curiosité.

La visite débute par le visionnage d’une vidéo qui a pour but d’introduire le contexte historique qui donne d’importantes clés de compréhension aux visiteurs. Particulièrement dense en informations, dates et personnages historiques, la vidéo peut s’avérer difficile à appréhender. Tout débute dans les années 1970 lorsque des trésors archéologiques sont découverts, c’est le Templo Mayor, lieu emblématique de cette civilisation qui refait surface. Mais pas d’inquiétude, la suite de l’exposition développe grand nombre de ces points dans un dédale de cartels d’exposition, d’objets et de cartes.

Utiliser des vidéos dans le cadre d’expositions à thématiques historiques permet d’introduire ou d’approfondir des sujets dans un format alliant plusieurs supports. En effet, le visuel joue un rôle prépondérant et souvent permet au public de se souvenir de certaines choses marquantes. La narration orale joue aussi dans la retention d’informations. Les vidéos sont présentes à plusieurs moments de l’exposition et traitent de multiples manières des archives Mexica. On y retrouve donc des explications historiques (comme évoqué précédemment), mais aussi des entretiens issus des chercheurs se focalisant sur le Templo Mayor ou de courtes vidéos sur des exemples de sacrifices.

L’objectif de cette publication n’est pas de vous divulguer la totalité des supports de médiations proposés par l’équipe derrière la muséographie et les nombreuses installations. Je souhaite évoquer un support particulièrement marquant quant à son contenu, mais aussi par rapport à sa forme.

Le calendrier rituel, appelé « Tonalpohualli », a une place de choix dans le voyage proposé par le quai Branly. Une grande reproduction dudit calendrier occupe l’espace comme une imposante statue au centre d’une pièce et se trouve placée devant deux écrans, présentant les explications des informations gravées à même la pierre. L’installation permet de comprendre les éléments charnières du calendrier tout en découvrant certaines déités et croyances des Mexica. La narration accompagnée de ce jeu de lumières et vidéo permet une immersion dans cet univers qui m’était inconnu.

Il serait dommage de ne pas mentionner l’importance donnée à tous les objets retrouvés au Templo Mayor présentés dans ce parcours. Vitrines, et présentoirs interviennent en simultanée avec les sculptures, cartes et graphiques pour ériger un circuit d’exposition étoffé. Assurément, une cohésion est présente. La société Mexica accordait une valeur indéniable aux symboles et à leur capacité fédératrice dans sa culture. On retrouve beaucoup de pierres volcaniques, mais aussi des bijoux dans un bel état de conservation, des métaux travaillés et des sculptures à l’effigie des dieux craints comme adulés. Pour approfondir ce point, les sacrifices humain étaient constituants dans une partie des rites présentés. Et l’exposition présente plusieurs récipients creusés dans des pierres monumentales utilisées pour récolter le sang, certains organes ou les os des sacrifiés. De fait, certains éléments sous vitrines peuvent choquer les publics non-avertis ou les plus jeunes. Ces sacrifices étaient réalisés pour pléthore de raisons, que je vous laisse découvrir.

Enfin, je souhaitais également souligner le rôle essentiel des cartels d’information présents tout au long du parcours tant il donne à chacun des détails nécessaires à la compréhension des outils, objets, sacrifices, coutumes et croyances présentés. Je ne peux que vous encourager à y mettre les pieds et à ouvrir votre curiosité à ce bout d’histoire de l’Amérique, c’est jusqu’au dimanche 08 septembre 2024 !

Chloé Schaeffer. Billet publié le 30/04/2024.

#Mexica#Quai branly#Musée#Paris#Sorties#ChloeHistoire#Histoirededire#Culture#Histoire#History#Mexico

0 notes

Text

Things from IWTV episode 10 (s2ep03) I noticed:

- the French is good this time! I still wonder if it's the actors themselves or dubbing. But it's actually understandable for a French-native person, and the language itself is exquisite. Wondering now if those lines are picked up from the book in Anne Rice's own pen, the translation of the books, or they're original lines written for the show by a French writer who has a splendid style.

- I just really loved the Armand flashback, both because of the language, and because it opens up the veil on the history of vampire covens throughout the centuries. Also we get to see more Lestat, this time Armand's Lestat and that's always a win.

- Armand is right about both Louis being broken and Claudia being pushed to the limits of how long she can accept this life of hers. I absolutely do not trust Armand, he's twisting the narrative for his own purpose (that I don't know because I haven't read the books yet), but still, he's a good judge of character. Can't not be one and survive for 500+ years I guess.

- the Loustat scenes, on the quai de Seine, in the bar and in the park, were insane.

- was that Sartre? Did. Did they just cameo'd in Sartre for the lols? Man, Paris.

- speaking of Paris, I know it was actually filmed in Prague, but man, I felt like I was back there. That Seine promenade, that's the one I walked countless times in my years living there. I could recognise the pavements like I was still there.

- Santiago's fed uppppp with Louis' BS. And he's definitely laughing at Claudia. Calling her "puce"... It's funny because in French, "ma puce" is a term of endearment, like "my darling", but indeed literally it means "my flea", so for an English-native like Claudia, it could be seen as literally being called the smallest, lowest member of the coven (like Delainey says in the episode insider), but for a French-native, it's like the coven is calling her sweetheart. And then they give her that dress and tell her she's going to play a kid for the bext 50 years, the one thing she hates being reminded of the most, and you go "ooooh. Oh, no, honey. They bad. This is bad." Clau's about to Break. Knowing how her story goes, I'm not sure I'm ready for that.

- Danny boy felt subdued this time. Like he's still reeling from Louis' invasion in the last episode, and now that Talamasca agent invading his laptop, he's feeling attacked on all sides and he's floundering to get back up again. That said, the scene with just him and Armand was particularly intense. You can sense how yearning Armand is, and how destabilised Daniel feels under Armand's gaze. In other words, that vampire really wanna fuck that old guy, and the old guy doesn't know how to feel about it but he's definitely feeling the intensity.

Need to read those books yesterday.

#rapha talks#rapha watches shows#interview with the vampire#iwtv s2#amc iwtv#iwtv spoilers#iwtv no pain#louis de pointe du lac#lestat de lioncourt#armand the vampire#daniel molloy#claudia de pointe du lac#loustat#loumand#armand x daniel#armandiel#armandaniel#(what's the actual generally accepted ship name for these two you can't tell me there's no consensus for a canon ship#that's been in existence for actual decades?)

168 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Imperial Prince riding his favorite pony

By Olivier Pichat

(History)

The Prince Imperial was trained in equestrian art by a loyal follower of the Emperor, Auguste Bachon, who quickly became his personal equerry. His daily training began at a very young age, as shown in a famous photograph by Mayer and Pierson, where the prince is tied to the saddle of his pony at the riding school on the Quai d'Orsay.This painting by Pichat, probably his first equestrian portrait, depicts him at around the age of four, already very confident on his mount. It was composed from two photographs taken by Mayer and Pierson at Fontainebleau on June 24, 1860.

One shows the child mounted on the same pony in front of the Gros Pavillon, the other seated on a chair, holding a boater hat. This second shot was likely staged specifically for the execution of the canvas. It was on this that the artist relied to portray the Prince Imperial, reproducing his pose, except for the crossed legs and his clothing. The prince is notably wearing a red striped kilt. Having Scottish origins, Empress Eugenie had traveled to Scotland in 1860 after the sudden death of her sister, the Duchess of Alba. Upon her return, she dressed her son in kilts, launching a new children's fashion. As for the pony, it is not Buttercup, the most famous of those in the prince's stable, but Harlequin or Polichinelle, two piebald ponies that the empress had purchased in Norway.

The painting was originally hung in 1861 in the office of Count Alexandre Walewski, at the Louvre Palace. Acquired from the Parisian art trade in 1996 with the assistance of the Society of Friends of the Château de Compiègne. Committee of February 15, 1996. Council of February 21, 1996. Entered the Château de Compiègne on March 26, 1996.

#louis napoléon#prince imperial#napoelon iii#empress eugenie#second french empire#napoleon#napoleon bonaparte#history

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Widening Gyre (Blades in the Dark Setting)

I’ve been running a Blades in the Dark game for about a year. But I didn’t want to run it in London and I instead wanted to talk about Australia and our Victorian history and things that were closer to my bones. To aid that, I made up a world.

Below the fold is twelve thousand plus words of me talking about a made up fantasy country modelled on Australia’s history for playing in Blades in the Dark. It has no mechanical information, just world information, and discusses ways to regard factions and history.

I cannot make it clear enough that below this fold there is a very large post and you may not find it interesting.

Ready?

Okay.

Introduction

The World and Peoples of Gyre

Forms of Factions

Districts of Gyre

There’s More

The History of Gyre, Told in Eight Governors

Faiths and Magic: The Miasma and the Sea

Cops Are A Ladder

Appenhelm

Centrum Tertiary

Copperquay

Districts Three (aka the Splay)

Eltham

Hundenrum Pass (aka The Hound’s Cradle)

Locke’s Quay

South Rocaphen (aka Rocaphen)

St Biscuiton’s Provided (aka The Cannery)

The Chantry

The Majestic

The Westery (aka The Westery)

Westcrook Abbeys

Wickstand

Landmarks

Gangs And Factions

Landmarks

Gangs And Factions

Landmarks

Gangs And Factions

Landmarks

Gangs And Factions

Landmarks

Gangs And Factions

Landmarks

Gangs And Factions

Landmarks

Gangs And Factions

Landmarks

Gangs And Factions

Landmarks

Gangs And Factions

Landmarks

Gangs And Factions

Landmarks

Gangs And Factions

Landmarks

Gangs And Factions

Landmarks

Gangs And Factions

Landmarks

Gangs And Factions

Introduction

The Widening Gyre is a Blades in the Dark campaign setting. Players take on familiar gang archetypes, but rather than scraping by in a city of perpetual night — modelled on a fantastical, British-inflected metropolis — Gyre casts them adrift at the edge of an empire that knows only how to extract.

Inspired by Australian history and shaped by perspectives from the global south, Gyre explores what it means to be both beneficiary and victim of empire. Built with convict labour, slave labour, and corporate abuse, the city stands atop crimes too vast for names, held in uneasy stasis by a community told the past is settled — because the guns have stopped firing.

The empire of Pentaragon doesn’t rule with grace. It flattens Gyre to fit its vision, wielding politeness like a cudgel and civility as camouflage. Cruelty here comes wrapped in softness — layered in etiquette, ritual, and red tape. The city teems with feuding powers, each ready to step over bodies to reach their version of order.

Gyre is a city where you can buy Ghost Insurance, but never a house. It shears the world’s wool, but shirts arrive by steamer. It boasts about ending slavery — and wants you to never mind the truth of how it ended, history deafened by the thunder of a warship to make it happen.

The World and Peoples of Gyre

This is a brief guide to the major nations that relate to Gyre, and the terms used for cultural backgrounds player characters can have.

Gyre is a coastal city-state clinging to the southern edge of Gyresend — called Djoddurra by its first peoples — the largest island in the Rustgold Archipelago, astride the Rusted Sea. Founded during the Grand Expanse, when Pentaragon carved its colonies from stolen shores, Gyre now churns out steel, wool, crops, and food for the empire’s hungry heart. In return, it imports machines, weapons, garments and almost anything that can be made out of those raw materials they export. There’s no consensus demonym for its people, since the island considers itself an extension of Actotum, though locals may be called Gyreish, and those born with uncanny, animistic traits are simply Bushweird.

Actotum, capital of the Pentaragon Empire, looms far to the north on Eidolon — a soot-stained island of gaslight trams, whale-oil engines, and architectural bravado. Its king sits on a throne of gold in a palace of platinum and has never even seen a poor person, his towers built high enough to never have to look down at the smog settled over the city. Actotum is the empire made manifest: machines thrum, proprietry is used to punish, and all the bread is made with the grinding of bones.

The island of Eidolon itself is a patchwork of nations under imperial thumb. Bannockburn to the north mines coal and drinks deep. Skellig lies west across the land-bridge, its stolen farmland the empire’s cradle. Tryk, a once-revered island of whale shamans, had its culture extinguished and its language extinguished in all but the most niche families. Deepclover, to the southwest, is starved by design to keep its hands cheap. Together they are Eideal, or Donners in the streets — but most prefer their roots: Bannair, Skellig, Thrun, or Meillion.

South of the empire’s gaze sprawls Muthira, a vast and varied continent, cosmopolitan and windswept, where horses carry more than people — they carry stories. Once the empire traded with coastal people for slaves, Muthira remains marked by chains, even after Emancipation. In Gyre, its people of a thousand different histories are all lumped together and called Muthirans, or Freesouls, among ruder terms.

Across the sea lie the Golden Colonies of Columbia — ten provinces masquerading as one, now risen in war over an empire’s broken promise to end slavery. Columbia claims it wants independence, but its hunger is familiar: it wants to keep its slaves, and has spent sixty years fighting the legal requirements of Emancipation until it all came to a head in this current war. After all, why should they not enjoy the same advantages as the Pentaragon empire? The steel and ships of Gyre now feed this fire. Columbians, to their enemies, are simply Rebellists.

Farther north sits Igutorsh, a frozen span once tapped for haunted whale-blood — before Gyre’s rise made it obsolete. Now, its peoples, the Torshic (or Tuskers, whispered low), draw inwards, and they are not a friendly land to the Pentaragon empire. If you see them in Gyre, they are a long way from home.

To the south lies the continent known dismissively as the Warring States — a fractured theatre of noble houses, shifting alliances, and rewritten histories. From Gyre, it barely registers. Yet every Stater (or Tawny, if you’re feeling rude) swears their land is the cradle of civilisation, and expects you to agree.

The Borsippan Provinces are the empire’s largest and most populous holding — dwarfing even Columbia and Gyre. Sprawled across the Cyrusic region, which claims more than half the world’s people, Borsippa is rich in silk, spice, and human resources that the Empire doesn’t care about too much if they can’t extract money from them. Imperial control here is tenuous at best; distance and diversity make for brittle chains. It was Borsippa’s weight that helped force the Emancipation — the empire, faced with a slave uprising in Gyre, risked wider revolt in Borsippa if it crushed the unrest, and gambled on peace instead. People from the Cyrusic world often carry regional names ending in -desh, though few make their way to Gyre’s docks.

Scattered across the empire are the Aleyn, a stateless diaspora driven from the Cyrusic lands by an ancient cataclysm. Most outside the Aleyn know very little about them, and what they know is usually told from the church, which speaks of them as the original people that opened the Three Gates that God keeps closed. Their presence is often misunderstood, and too often unwelcome.

Finally, the Xalawa are the first people of Djoddurra. Their name, meaning Tallship People, marks those whose ancestors stood on the soil when the empire’s ships arrived — and the slaughter began. Generations of erasure have left their cultures fractured but not broken. Storytelling, lineage, and memory bind them, and many local names come from their tongue. It’s also from them the word migulu comes: sometimes translated as “soulless,” sometimes “those white folk,” always spoken with purpose.

The History of Gyre, Told in Eight Governors

Jac “Dancer” Dampiere — The Pirate Who Dreamed

Before Gyre was a colony, it was a crossroads — and Jac Dampiere was its first self-styled governor. A biracial pirate, Dampiere helped found a port in the remote island, not with imperial mandate but with charisma and cunning, even forming an alliance with the Xalawa natives of the island. He built a trade network that thrived on freedom and fluid loyalties, a system too wild for the empire’s taste. Eventually the time came to make the Eidolon holdout a proper colony, and Dampiere was graduated from pirate to explorer, offered either a noble title, or a dance at the end of a rope.

When the decision came to turn Gyre into a slave colony, Dampiere was diminished in history. It is only recently that Dampiere has been represented in art of the governors, to try and resuscitate the history of the founding.

Ront Eltham — Oppressions’ Architect

Where Dampiere saw opportunity, Ront Eltham saw order. The empire’s first “proper” governor, Eltham arrived with chains and blueprints. He built the prisons, the mines, the labor camps — the machinery of colonial exploitation. A man of conviction and cruelty, Eltham believed he was civilizing the land. He died in office, proud of the scars he left behind. His name now adorns the richest district in Gyre, a bitter irony for those who remember the cost.

Fedder Oisin — The Silent Lash

Oisin followed Eltham, but left no monuments. A forgettable figure, remembered only for the lash he carried and the silence he enforced. His rule was a pause — a breath held between tyrannies — and history barely bothers to speak his name. He’s particularly noteworthy for having done very little writing of his own, where most governors left volumes of text behind in the form of letters and minutes to meetings. Traditionally it’s held that Oisin’s rule is when the first slavetaker business and prison guards were formed into police stations.

Willy Harcourt — The Sinking Captain

Harcourt was a naval man, rewarded with governorship as if Gyre were just another ship to command. He believed discipline and hierarchy would tame the city. But Gyre is no vessel — it leaks, it resists, it mutinies. Harcourt failed to break the unions, failed to impose order, and failed to understand the land he ruled. His tenure is remembered as a slow-motion wreck. Particularly, many of the union battles happened under Harcourt.

Gris Huntrum — The Finest Tyrant

Born in Pentaragon but raised in Gyre, Huntrum was the first governor with local roots. He understood the city’s rhythms — and used them to consolidate power. He transformed the Governor’s Estate into the Majestic, a fortress of opulence and control. But his legacy was not built to last; the laws he built to control the union pushed them to work together, the plantations he established to enrich his people helped foment revolution, and even the Majestic was shelled during the Copperpalm Uprising to need rebuilding. Huntrum’s rule was a turning point — the moment Gyre’s elite began to look inward, and downward, with fear. Huntrum was renowned for increasing and conslidating police power to try and prevent slave uprisings and the growing cooperation with the slaves and Xalawa natives.

Lote Knight — The Catalyst of Rebellion

Lote Knight was a man of failures, a storied career full of new positions, new opportunities, and absolutely disastrous failures at each one: he was a failed explorer, a failed colonial administrator, and a failed suppressor of rebellion. His exploration expeditions found islands that were already discovered. His first colonial settlement mutinied against him and sent him back to Actotum in his personal schooner. Then, he was sent to Gyre. Within eighteen months, he ignited the Copperpalm Uprising — a two-year period of local rule where the former slaves of the Plantations took the Majestic as their own fortress. Knight was sent out of Gyre on a mail boat, and once in Actotum, was promoted sideways into a naval command, and eventually fought in the defense of Columbia, before being convinced to join the Columbian side, followed by a traitor’s hanging.

While most Governors’ first names are regarded well, it’s worth noting you’ll probably never meet someone named Lote in Gyre.

Vittner Paul — The Iron Return

Then came Vittner Paul. Sent from Actotum with the full force of the navy, Paul arrived with carrots and sticks. On the one hand, he came with lawyers and bankers to do full legal recognition and infusion of cash and contracts for the colony, and the full legal rule of Emancipation. He came with the permission and resources to establish a mint, a central bank, social infrastructure, regulations and the redistribution of land and resources to freed slaves. He also brought these things at the helm of a destroyer that shelled the city, so thoroughly that several parts of the city still have buried unexploded shells in them. This is known as the Reconsolidation or the Restructuring.

The rich hate Paul for destroying enormous amounts of wealth; he freed slaves, he gave unions freedom to meet and permission to negotiate, and required convict labor teams be paid. He instituted huge public works projects, including plumbing and sewage, and even built flop areas. Plantations were handed over wholesale to the slaves that had built them, and even the largest and most valuable one was given to its community wholesale and even given freedom to be its own police district, which is now the Westery. The poor hate him because again, he shelled everything, and many of his public works projects were about destroying the power of unions to provide the same services.

A bureaucrat with a boot, Paul is remembered as a bastard’s bastard — efficient, brutal, and universally despised. He rebuilt the Majestic, rewrote the laws, and rewrote his own history.

Killdeer Maquisdeux — The Steward of Decline

Now, Gyre is ruled by Killdeer Maquisdeux. Rhetorically, he positions himself as the gentle hand to steady a tumultuous land during a difficult time. Actually, Maquisdeux governs not to build, but to manage what he sees as the slow decay of empire. With the Columbian colony falling and the Cyrusics growing discontented with the Actotum rule, he sees the Empire as slowly crumbling, and therefore this city is a sinking ship. Unable to abandon it, he instead intends to spend as much time in the dining hall enjoying himself as possible. The man is invested in the hedonism that is deeply aware that the end is not a question of if, but when. As long as he can balance the books and pay for the demands of Actotum, the only project he cares much for is the ongoing indulgence of his hobbies and tastes.

Faiths and Magic: The Miasma and the Sea

The dominant faith across Gyre and much of the empire is the Church of the Three Gates—a devout, doctrinal reshaping of older Aleyn beliefs. It teaches that all unnatural forces in the world—magic, madness, unreason—emerge from a corruptive veil known as The Miasma. Miasma is a catch-all: a name given to anything that doesn’t fit tidy imperial logic. Visions, hauntings, inexplicable luck, or bodies that change shape—Miasma all. The Church claims to contain it. The ghosts that people Gyre? While the Church recognises that spirits are real, any spirit that lasts more than a few moments is clearly an impression in the Miasma of the dead person, and should be dealt with quickly.

To that end, the Church fields Medicants, robed administrators who “manage contagion” wherever Miasma is suspected. In practice, this means targeting medicine-makers, spirit-workers, and shamans—especially those tied to Xalawa and other indigenous traditions. Containment can mean quarantine. It can also mean napalm. Purgigants, great flamethrowers carried in brass and iron tanks strapped to the back of the Medicants, are sometimes used to burn out “sites of contamination,” whether they be shrines or whole homes.

Where faith fractures, cults bloom. Some are just zealots who turn Church dogma into purge and prophecy. Others reinterpret the Three Gates entirely—remaking it with different saints, symbols, and sins. Still others reject the Church outright and tap into stranger dreams, older gods, and powers the empire never catalogued.

Magic in Gyre isn’t an abstract system of rules—it’s something the world does when no one’s looking. It reveals itself in four distinct ways:

Sea magic wells up from the Rusted Sea and swims in nightmares. It births mutant, leviathanic demon-whales—creatures of muscle, voidlight, and unrelenting hate. Not unknowable, like something Lovecraft might conjure—just furious. An elemental spite given form.

Soil magic is the domain of the Xalawa, bound to land, body, and tradition. It grows through ritual, shapeshifting, healing, and sympathetic bonds. It is quiet, persistent, and deeply rooted—even after generations of assault. Since people are superstitious about the Xalawa’s ability to do these things, they hide their craft from everyone.

Stone magic lies buried beneath the city and seabed: ancient, cryptic, and hungry. This is the magic of long-dead civilisations or things that were never alive in the first place. It obeys no pattern and speaks in accidents—gravity failing in one room, or shadows moving on their own. Stone magic ritualists often know only one great thing, and that secret breaks them.

Church magic denies it is magic at all. It cloaks itself in reason, logic, and light. It operates quietly—chance bending just so, a bureaucrat spared by unexplainable luck, an addict suddenly clean. It abhors spectacle. If anything strange happens, it claims it didn’t. Many of its practitioners don’t think there’s any magic to it at all – just miracles given to those who trust in what holds the three gates closed.

Then, of course, there’s the category of the Bushweird. People in Gyre, who were born in Gyre, have a chance of being born with some animalian traits, like the ears or eyes of an animal as part of their body. Bushweird are common and vary in their degree of obviousness – but it’s pretty obvious that the northern suburbs, with the rich estates and police presence, have no Bushweird presence, and even more animalistic Bushweird wind up driven out of the city.

Gyre as Land of Stolen Labour

Gyre began as a prison colony. The first to arrive were the convicted and their guards: labourers and executioners both. While prisoners broke rock and built roads, their overseers waged the first campaigns of genocide against the Xalawa people. When the Pentagon Trading Company formalised the colony’s economy, Muthiran captives were imported in chains—slaves for the empire’s farms and fields. Together, the enslaved and imprisoned drove Gyre’s early growth.

Over time, prisoners (primarily from Actotum, and therefore, often white people with backgrounds in industries before their deporting) forged unions and dominated mining and construction. Meanwhile, enslaved labour fed the boom of agriculture—especially in the fertile band now called the Balm. But as the enslaved population grew, it became a political liability. Sixty years ago, there came two incidents in Gyre, close together; the Copperpalm Rebellion or Revolution, and then the reconquering of the city by the Empire, known as the Reclamation.

The Reclamation came with a new edict, the outlawing of slavery in an incident known as the Emancipation. Gyre’s population surged by a quarter overnight. One in four citizens had been enslaved the day before and that was just in the city – many, many more slaves lived out in the surrounding islands and on plantations. Emancipation reshaped the city’s fabric—and ruptured the empire’s. Freedmen’s rights bred fury. Exploiters fought back. Without slave labour to drive industry, the rules around convict labour were tightened and suddenly, many free souls were conscripted in labor gangs.

Even that was just a temporary solution in Gyre; across the sea, in Columbia, the colony initially delayed Emancipation, then eventually rose to reject it wholesale. That situation has grown into outright war, all while in Gyre economic disparity has grown worse and worse. The dream of freedom has curdled: five percent own ninety-five percent, most Freesouls have no wealth at all, and mobility is a rumour.

Gyre is far from the frontlines of Columbia, but its drydocks ring with hammer and flame, forging ships for a war it didn’t choose.

This is the now—an age of imperial retreat, tightening fists, and doors that only open from the outside.

Forms of Factions

Before delving into the factions and districts of Gyre, it’s important to understand that factions in Gyre serve different ends rather than just being ‘gangs.’

Gangs in a Gyre campaign are not simply generic blocks of criminals that intersect with one another. Rather, the nature of crime in Gyre is one where a criminal gang is seen as a form of surrogate government; they do something to consolidate power, they offer their territory something that the overarching ‘legitimate’ authority doesn’t.

That is there are Gangs, who are trying to maintain territory and control through any means, legal or not, there are Unions, who are trying to maintain territory and control through legal means (and maybe a little illegal means), and then there are Institutions, that do not have to care about the law. Finally, there are also Cults, which follow similar methods to gangs, but do not necessarily care about having access to power and control; their power and control is instrumental to some other end.

All police forces are Institutions. Institutions are powerful and ponderous. You can’t kill an institution by killing its members; anyone who dies in the institution will be replaced and they take killing very seriously. The Royal Guard are also an institution, as a kind of police force that can go anywhere in the city, and the Navy, while centered in Locke’s Quay are also an institutions.

It’s very hard to improve your reputation with institutions. They do not have pity or personality and are large enough that any individual friend you have in them cannot exert meaningful power over the whole. No amount of goodness from one good cop can ever make the cops as a group stop beating up people they think are making too much of a fuss. Similarly, if the Navy wants you arrested, you can’t do favours for them until they forget about it.

By default, you cannot increase your reputation with Institutions. You can only be forgotten about them, when the gang’s wanted level decreases.

Then there are Unions. Unions are much like gangs, and indeed, interface with gangs, but can have conflicting wants with gangs. By default, unions want businesses and industry to keep functioning, even if those industries are bad. The Wellhawks of Rocaphen are working class, anti-police, and fought to ensure that people have freedom to move without police detainment on the way to work. They also want to privatise the water towers, because that was where their power originally stemmed. Similarly, a union whose industry dries up can be left with a body of loyal people who have nothing to do. The Zookeepers started out as the Mancatcher Union and now they’re a racist street gang.

Still, what unions offer gangs is stability. A gang has a hard time handling as many companies or institutional wealth or power by comparison to unions. A good example is the Roasters, who serve as a union of coffee shop owners in the Hound’s Cradle, but who almost exclusively deal with other gangs, using the Beasts of Gevaudan for enforcement and using their transport connections to help move goods for the other gangs in the area. If you can do business, and you’re not bad for business, unions are very powerful friends. They can even make great patrons. Another example of a symbiotic gang-union relationship is the lumber union in the Splay, who are pretty tightly connected to the Chettes gang in Wickstand. The meeting hall for the union is far away from where any cops care to act, so Chettes can use it for meetings and storage, but the lack of business in the Splay for them means that they don’t stay there. Similarly, the Union’s official status means that it’s easy for Chettes to lean on them for legal protection against Institutions like police.

Finally, there are Cults. Cults exist in a space that’s not-quite-a-gang but not-quite-legal; they don’t want attention from Institutions and have inscrutable wants and needs, but they very much can’t treat the systems of power the same way a Union can. Even the Cults that are part of the church can’t necessarily rely on the power of the church. Cults need to be sneaky and extremely driven by connections: You may know a cult because of a person in it, not because of the way they fly their gang colours.

These faction types are all non-overlapping. You can be a Naval officer who’s secretly a member of a gang and also in a cult, but who has a strong tie to the union he used to be in. These are all possible relationships. Just they all put demands on you. Most of them are treated in layers of legitimacy, too; Institutions are more respectable than Unions, which are more respectable than Gangs, which are more respectable than Cults.

Cops Are A Ladder

The nature of policing in Gyre is descending authority. That is to say, there is a pretty reasonable sequence authority from location to location. If you do something in Wickstand, then head to Locke’s Quay and lay low for a little while, the police in Locke’s Quay don’t answer to the police in Wickstand.

There are exceptions; almost nothing can make the police of the Hound’s Cradle do anything. The Splay doesn’t really have its own police, which means that seeing any of the three connected districts acting means someone above them started it.

Broadly, it works out such that districts can make demands of the police beneath them in this kind of structure:

ElthamCopperquayThe ChantryWestcrook AbbeysSouth RocaphenLocke’s QuayWickstandAppenhelm

The Cannery, the Westery, the Centrum Tertiary and the Hound’s Cradle are somewhat special cases.

The Cannery is a private business residence and therefore asserts that no police authority holds within the district. They instead rely on Gripp & Pipe Human Resource Management, and they deliver subjects to the police. They just as much try to disappear police investigating in the Cannery.

The Westery has one police officer, Clem, and she is a detective who engages in community policing. She no doubt receives requests from neighbouring district police, and promptly loses them in her bungalow.

The Centrum Tertiary’s police force only have authority on trains and in the station, but that leaves large parts of the district that are technically the authority of someone else, usually Wickstand.

The Hound’s Cradle police force is so well-financed by the nobility and so functionally powerless that their only job is losing information that would embarrass rich clients of the businesses in the Cradle.

The Royal Guard serve as the cross-district police force, as free agents, and can throw their weight around freely. They are non-districted, and tend to form small strike forces to investigate specific problems. Killing them will only yield an institutional response.

Districts of Gyre

Gyre is divided into two major regions, with a river running between them. The northern half of the City is divided into Eltham Font, Copperquay, The Chantry and the Majestic, with the southern, poorer districts comprising Westcrook Abbeys, Wickstand, South Rocaphen, St Biscuiton’s Provided aka the Cannery, Districts Three aka the Splay, Locke’s Quay, Appenhelm, the Centrum Tertiary, Hundenrum Pass, and The Westery.

Appenhelm

Appenhelm is the closest suburb to the Doldridge prison and functions as its effective dumping ground. It’s where fresh convicts are disembarked, then discharged convicts end up — a place of marginalization, survival, and quiet desperation. The district is defined by its proximity to the prison-industrial complex and the social decay that trails behind it.

Landmarks

Appenhelm Station — The station and post office, and technically part of the prison administration, Appenhelm Station is the one large, well-decorated and protected building in the district. The decoration is all on one side, where the back is covered with graffiti.

Bilge Market — The worst and lowest fence of the city. Bilge Market is the most unregulated place to trade in the city, and it’s full of con artists and scheisters. On the other hand it is how you can get things into the prison and how you can get things out of the prison. It’s nasty and brutish and it’s foul, and it sinks. Despite being atop a hill that can see the Cannery, the common line is that ‘Bilge is downhill from the cannery,’ because of the smell and the way stolen goods end up there.

Churn Lane — The prison does mining and industrial work, mostly some forms of refining for ransport. The waste from that is then brought it to the shore via the convict train and vented into a ever-burning pit in the mainland, around which has been built the horrible stone and wood street Churn Lane. Convicts scrape and fish the industrial waste for precious goods or sellable materials.

Forks Teeth — A jagged outcrop of stone on the edge of town. It’s a landmark in the classic sense – people know about it and use it to orient themselves and meet up.

Harrow’s Barrow — A grounded barge from the Stonehook days, Harrow’s Barrow has been pulled up on shore and is the closest thing Appenhelm has to a gaming/pleasure district. You have to walk down a long winding path to Harrow’s Barrow, and the path being uneven is seen as a good way to keep drunk convicts in the Barrow gambling and spending the little money they have.

Stonehook Crossing — Before the Doldridge had a train station and bridge, prisoners were transferred to the prison (at the time just a mining labor camp) by boats. Stonehook is the last remnant of the huge transport dock, designed to marshall and funnel convicts to it. Over the decades its dilapidation has led to steady dismantling of all the buildings and structures on the dock. There’s a joke that the cons steal even the nails as they take Stonehook apart, piece by piece.

The Brinehouse — Secondary processing for the prison’s industrial goods. Brinehouse is a place cons can get some work, but there’s no meaningful protections and it involves handling and breathing a lot of nasty materials. The fear is if you fall into the vats at the Brinehouse they’ll never even know you died. Still, if you can handle bricks of metal coated with a powder that burns your lungs for a few dollars a week, it’s work that you can do.

The Last Resort — A barely-standing church built from scrap metal and whale vertebrae, where the outcasts of Appenhelm seek solace. It’s not a cult, per se, but it’s hardly orthodox to the Three Gates. Its ex-convict priest, a long tripper, has lost his eyesight and now preaches about redemption, survival, and the cruelty of the world beyond the Doldridge, which takes the form of familiar church lessons, but definitely don’t come directly from the sciptures. The hope he has to offer is small but he takes it seriously.

Gangs And Factions

Appenhelm Constabulary – Former prison guards turned local enforcers. They treat everyone like a convict and lack the numbers to project real power. Very obsequious to even just the basic middle class and beholden to larger gangs that use Appenhelm for staging grounds.

Deepest Eye – A doomsday cult driven by whispers from beneath the Doldridge. They believe in omnicide and seek to spread a plague. Haven’t found a plague suited to the purpose yet, but they’re trying.

‘Apless – Pronounced “hapless,” this gang is the prison’s shadow network, focused on smuggling and influence both inside and outside the walls. There’s a lot of them, but they aren’t very well connected – ‘Apless don’t tend to come to each other’s aid outside.

Barbery – A protection racket that controls corners and extorts locals. Sometimes confused with the Auntie Jacks, since they both evoke barbers, but the Barbery are just goons with knives.

Long Trippers – Ex-prisoners who believe they’re just passing through. They run scams involving transport, mail fraud, and navy impersonation. You can usually tell a Long Tripper because they aggressively resist local slang and accents, and since they’re all born outside of Gyre, there aren’t any Bushweird in the gang.

Centrum Tertiary

Centrum Tertiary is the railyard heart of Gyre — a district that officially has no residences, yet teems with life. It is a legal grey zone, a place where the city’s infrastructure, commerce, and shadow economies intersect. Beneath the rails lies the Underrail, a subterranean bazaar lit by whale-bar lights, where the technically-unhoused, the exiled, and the entrepreneurial thrive. It is a place of movement, secrecy, and survival.

Landmarks

Catcher’s Cabins — The Catcher’s Cabins, once used for mass transport under brutal conditions, were officially decommissioned, but never destroyed due to cost. Left to decay in forgotten trainyards, they’ve become dense, makeshift housing for squatters and ex-cons.

Centrum Ward — The Centrum Ward’s head office is also known as the Centrum Ward. Officers here draw wages as police force, but their authority only extends to the trains and the stations – meaning that even just outside the station is a grey area for their authority. Their presence is strongest around train yards and the Underrail, where they keep a keen eye on illicit transport deals and counterfeit travel passes. Basically, if you can’t see one, you can probably get away with anything.

Scissor Row — The two forking lanes that reach around Underrail, Scissor Row is for people who can’t manage a permanent business and don’t have the money to pay into the fund for space. This is the kind of space Backtaggers set up pop-up shops. Also because of its shape it’s not hard to ditch the goods and escape if you’re rumbled by police or criminal rivals.

The Gilded Chain — One of the last warehouses with a known brand, because the Westery demands this brand never be forgotten. Gilderoy Holdings made the Gilded Chain, which was a warehouse for storing their ‘Labor Cargo.’ The Gilded Chain offices are essentially a public square for people, but overwhelming it’s favoured by Mithuran people and folk who visit from the Balm.

The Highest Time — The Centrum Tertiary’s clocktower is the central headquarters of the High Timers, and also the home of a specialised doctor who operates out of the peak of the building.

The Iron Chorus — A converted train carriage that functions as a music hall and gathering place. It’s got a pipe organ built into it from a converted engine.

The Ratwell — A section of the Underrail known for its cramped stalls selling suspicious wares — expired medicines, scrap-tech, and bootleg whale oil cartridges. Caveat Emptor!

The Sweepyards — The sprawling train storage yards where abandoned, broken, and illegally modified train cars sit in shadowed corners. The Centrum Ward patrols the area, but there are plenty of blind spots where gangs set up temporary operations or stash contraband.

The Transit Mortis — There’s one train line that runs up to Appenhelm then across to the Balm, meaning it was one train line that transported many tragically destined, abused people, convicts and slaves both. The line is regarded to be cursed.

The Underrail — The Underrail is an underground bazaar where ex-convicts, travelers, and locals do business. It’s lit by whale bar-lights, all under-cover with the only light from outside coming through the rails above. The stalls offer everything from salvaged mechanics to street food, while gang enforcers and Centrum Ward patrols keep a measured distance, respecting the neutrality.

The Wayhouse — An old maintenance depot converted into an unofficial transit hub for those looking for off-the-books transport. The closest thing the Backtaggers have to a headquarters, which is why it’s decorated in their three main colours.

Gangs And Factions

Centrum Tertiary Crossing-Guards – Technically a police force, these are the ticket keepers and station enforcers. Their motto might as well be “not my problem.”

Backtaggers – A graffiti gang and crew of bravos who value visibility and style. They’re known for starting fights and winning them.

Underrail – The ruthless management of the Night Market. They control supply lines and enforce their dominance with brutal efficiency.

High Timers – Drug dealers who specialize in long-distance smuggling of organic goods from the Balm. They operate with patience and deep pockets.

Deadstops – Assassins who specialize in ghost containment. They kidnap targets and send them south on trains, ensuring their ghosts don’t haunt Gyre.

Copperquay

Copperquay is the administrative and financial heart of Gyre — a district of power, wealth, and bureaucracy. It houses Parliament, the city’s largest banks, the central police station, and the palace guardhouse. The architecture is grand, the streets are clean, and the scent of perfume masks the rot of politics. It is where laws are made, fortunes are traded, and secrets are buried beneath layers of civility.

Landmarks

Bastion Precinct — The central police station of the city, Bastion Precinct is a brutalist monolith of grey stone and mirrored glass. Technically, Bastion Precinct is the central police headquarters, and it holds the largest temporary prison in the city, numerous records, and is seen as the seat of authority for all the cops (but Clem). It even has a Royal Guard liaison.

Langford Auctions — An opulent, high-security auction house dealing in rare artifacts, ancestral heirlooms, and occasionally, people’s futures. Langford’s is where fortunes are made and lost in a single bid. Famously, it’s the largest purchaser of champagne in the city, because it uses it for so many formal events.

Parliament House — A grand, sea-facing structure of sandstone, chalk and ivory, Parliament House is where the city’s laws are debated and power is bartered. It’s renowned for being heavily perfumed (because the imported seats and upholstery in the building handle the humidity badly and smell bad).

Penghalion’s Pledge — At the center of Copperquay’s main plaza stands a baroque fountain of a weeping woman cradling a leviathan skull. Sometimes, donations can be found sunk in its water, and left around its base – bones, jewels and coins.

The Palace Guardhouse — A ceremonial and strategic stronghold, the Guardhouse is home to the city’s elite protectors of Parliament and the judiciary. Its members wear armor etched with sea-sigil runes and carry weapons blessed by both state and church. The Guardhouse is neutral in theory, but it absolutely turns as the Royal Guard edict.

The Vaulted Exchange — One of the two largest banks in the city, the Vaulted Exchange is a fortress of finance — its walls reinforced with copper and coralcrete. It’s where trade routes are insured, debts are bought and sold, and the city’s economic lifeblood is pumped. Notably, it has Mint privileges, and is the producer of the city’s Plaque currencies.

The Whisper Vault — An underground speakeasy and information exchange run by the Gargoyles. Hidden behind a false wall in a shipping office, it’s where secrets are traded like currency. The Vault is soundproofed with whalehide and lit by bioluminescent jellyfish tanks.

The Whitehall Pavilion — A graceful riverside structure built from pale sandstone, and chalk. It is officially a public archive and cultural center. Locals come here to read, reflect, or attend lectures on civic history, around a shimmering pool from the river. The Pavilion’s acoustics are strange; whispers carry too far, and sometimes the water speaks back.

Gangs And Factions

Copperquay Constabulary – A powerful mix of constables and royal guards. Possibly the most far-reaching law enforcement presence in the city.

Gargoyles – A criminal syndicate embedded in day jobs like food service and window cleaning. They observe, record, and trade in secrets.

Baptisers – A hyper-devout cult with ties to the Church, more zealous than the mainstream faith. Imagine if Jesuit monks were also Kung Fu munks, but also Sovereign Citizens.

Xaos Howl – Mentioned by name, but details are scarce — likely a shadowy or esoteric faction operating in the margins.

Districts Three (aka the Splay)

Legally, not technically a single district, it’s a place that intersects a bunch of connected districts so the police bicker over responsibilities. It is therefore, the heart of gang and crime activity

Landmarks

Boggrell Deeps — The river that runs underneath much of the Splay runs deep at the bottom of rifts in the rock the city has been built over, giving long drops and ‘under street’ spaces. Boggrell Deeps has its own deep people, cultists and weirdoes, and also just uh, a place to disappear bodies. Notorious for fights.

Hacksaws’ — The defunct loggers union hall which is now mostly frequented by heavies, goons and disorderlies looking for some way to make money. Notorious for fights.

Redbend Rounder — A twisting stretch of road marked by skid burns and wreckage, serving as the Bugknives’ main patrol. If you need to find a bugknife, you can probably find them if you head to this lit up district. Notorious for fights.

Sart Sales — A hawker’s corner and pawn store famous for a constantly defaced sign. Unlike the Underrail, you can almost always never see the same sale here twice – the business itself is practically vestigial and mostly known for the sellers outside kicking back to the owners. Notorious for fights.

The Breaded Basket — A crumbling, multi-level tenement where the Corkies operate under the guise of a community help center. Information is siphoned in and out of its walls, with residents unwittingly selling their privacy for small comforts like food, security, or forged documents. Notorious for fights. Notorious for fights.

The Emberfold — A half-burned warehouse where the Boiler-Rats run their gambling dens. Games range from blood sport betting to intricate cons, and outsiders risk being swallowed whole if they can’t keep up with the stakes.

The Hollow Hearth — An abandoned industrial boiler repurposed into the Rustjacks’ central distillery. Its pipes run deep beneath the Splay, carrying illicit red liquor to secret caches across the district. Notorious for fights.

The Teetertenner — A ten storey tall apartment complex built out of two buildings slowly creeping together across a steep cliff in the Splay district. The two buildings merged into one misshapen tower that also represents a bottleneck in the district, with multiple layers spreading out from its core, creating part of the spiderweb of the Splay. Notorious for fights.

Gangs And Factions

Districts Three Police — There’s no technical police force of Districts Three, but rather whatever Westcrook, South Rocaphen, Wickstand can spare.

Corkies — Freaks Only’ criminal organisation that just so happens to have extremely photogenic leaders.

The Real Corkies — A small core of agents operating out of the Corkies doing information brokering.

Tannersaws — Muggers, gangsters and rowdies subordinate to the Cannery gangs

Boiler-Rats — Pickup gang in the Splay taking advantage of a void, running books and controlling hoppers

Rustjacks — Hawkers selling bootleg hooch in the Splay. Their booze is typically coloured red.

Bugknives — Kamen Rider Bravo Bozos. Self-styled community watch who want to protect people in the splay, riding on modified bikes to get into fights quickly.

Eltham

Eltham Font is the crown jewel of Gyre — a district of wealth, legacy, and quiet power. Built from stark white sandstone and lined with tall, elegant trees, Eltham is a place of prestige and privilege. It sits on the riverbank opposite the ocean, close to Copperquay, and is home to the city’s elite: scholars, nobles, and the politically connected. The district exudes refinement, but beneath its polished surface lies a web of manipulation, entitlement, and youthful rebellion.

Landmarks

Ashcroft Pier — A quiet but strategically placed dockside used for discreet naval operations. By night, smugglers whisper that the Bluecloaks use it for dealings that never make the official police ledgers.

Coastal College — The city’s elite university, where scholars, heirs, and politicians-in-training shape their futures under watchful faculty. Its sandstone halls echo with tradition, while hidden student factions — possibly the Majesties — maneuver in the shadows.

The Beacon of Dominion — A towering bronze monument commemorating the empire’s naval supremacy. Some admire it, others question the quiet military presence always lingering nearby.

The Ellford Museum — A stately institution filled with maritime artifacts, royal decrees, and the preserved records of Eltham’s founding families. The Bluecloaks monitor its archives closely, ensuring certain histories remain buried.

The Halewick Gardens — A sprawling public garden adorned with exotic flora, regal promenades, and carefully curated water features. It’s a place of leisure for the wealthy and a retreat for academics escaping the rigidity of Coastal College.

The Highspire Amphitheatre — A grand, open-air performance space carved into the hillside, where operas, speeches, and political debates unfold beneath the sandstone-clad skyline.

The Rook’s Promenade — A winding riverfront boulevard lined with fine restaurants, scholarly retreats, and dignified townhouses. Chances are if you see a fight here between young people it’ll get blamed on ‘The Ellraisers’

The Veil District — A cluster of imposing mansions whose owners remain elusive, linked by cryptic business ventures and private gatherings. The Majesties are rumored to meet here, but no proof ever surfaces.

Gangs And Factions

Eltham Font Constabulary – Well-equipped and well-trained, often composed of Navy veterans and privileged second sons. They maintain order with quiet efficiency.

Bluecloaks – A gang embedded within the police force. They monitor, manipulate, and suppress inconvenient truths.

Ellraisers – The rebellious youth of the elite. They engage in criminal mischief for thrills, often protected by their family names.

Majesties – Political conspirators and manipulators. They operate in the shadows, influencing the governor and shaping the city’s future through smuggling and information control.

Eltham Student Body – While not a gang per se, the student body of Coastal College is a political force in its own right, with factions and rivalries that spill into the city.

Hundenrum Pass (aka The Hound’s Cradle)

The smallest district in Gyre — just one street long — Hundenrum Pass is a paradox of power and permissiveness. Known as The Hound’s Cradle, it is a haven for artists, bohemians, political dissidents, and red-light workers. Despite its size, it generates immense wealth and cultural influence. It is a place where rules bend, masks are worn, and secrets are traded in plain sight. The police are well-funded but largely powerless here, and the community polices itself — flamboyantly, fiercely, and with flair.

Landmarks

Brickery Song — Technically, an inn with in-house entertainers, the only permanent residents are the freesoul family living there. A tall multi-storey house, people rent time there by days, but only stay there by hours. It’s not a sex shop – it’s known for music, food, and art.

Tarmin and Anzims — Most businesses in the Cradle are kind of single-purpose; theatres owned by one small company, bars with one speciality, sex shops with specific workers. Tarmin and Anzim are notable for being a place with rotating contributors.

The Cauldron — A longstanding lesbian bar founded in the basement of an old sewer plant, renowned for witch vibes.

The Hound’s Pigs — The police station of the Cradle. It is the most well-paid police station in the city. It has a truly abysmal arrest rate. The police complain constantly about the unhelpful community, but are financed well (to make records disappear)

Gangs And Factions

Cavorters – A cult devoted to endless indulgence and ecstatic ritual. They perform bimonthly human sacrifices and are building a god from noble body parts.

Beasts of Gevaudan – The de facto community police. Styled like pirates, they take a modest cut from local businesses and ensure order. They wear denim jackets with their name emblazoned on the back.

The Roasters – A union of coffee sellers who once held exclusive rights to the district’s coffee trade. Now a powerful and organized economic bloc.

Hundenrum Pass Constabulary – Technically the police force here, but with little real power. They mostly extract people from situations rather than enforce laws.

Jamskips, Rollers, Windowblacks – Mentioned by name but not detailed. Likely minor or specialized factions operating in the Cradle’s unique ecosystem.

Locke’s Quay

Locke’s Quay is Gyre’s dockside district — a chaotic blend of industry, nightlife, and maritime grit. It’s where the city meets the sea, and where the rules start to blur. Tattoo parlours, concert halls, and pleasurecraft line the waterfront, while smugglers, sailors, and syndicates move goods and secrets under the cover of salt spray and moonlight. It’s loud, lawless, and alive.

Landmarks

Her Majesty’s Finest Shipyards — A chaotic sprawl of ship construction sites, where half-built destroyers loom over workers hauling rivets and plating. The Navy controls access, but smugglers bribe their way in, slipping contraband onto vessels before they’re even seaworthy.

Huntrum Tower — A looming government office overlooking the docks, where naval officers dictate ship movements and recruitment orders. It’s a fortress of bureaucracy, but its records — if one could get to them — hold damning secrets on forced conscription and hidden wartime dealings.

Sirens’ Landing — A lavish waterfront hall run by the Sibs of Siren, serving as a pleasure den and information hub. Officials, gang leaders, and even constables drift through, indulging in its intoxicants while slipping requests for intel across polished counters.

The Black Piers — A stretch of docks that rarely sees daylight, where the Ironhatch load their barges under moonlight. The air reeks of salt and oil, and whispers of disappearances linger in the night air like ghosts clinging to the tides.

The Briny Chapel — A decrepit, salt-eaten chapel where sailors leave offerings to old sea gods and mourn those lost to the depths. Overseen by a priest with faceblindness.

The Cutlass Row — A long strip of dockside workshops where shipwrights modify vessels for speed, stealth, or smuggling. The Naval Gazers frequent these shops, outfitting their personal crafts with hidden compartments and reinforced hulls.

The Keel’s Haul — A dense, open-air trading ground where shipbuilders, sailors, and pirates alike come to barter for supplies. Everything from stolen naval equipment to forged documents passes through its stalls, unbothered by law enforcement.

The Scuttler’s Arms — A pub with walls scarred by blades and bullet holes, favored by Naval Gazers and mercenaries. Dockside deals are struck here over strong liquor, and every patron knows that speaking too loudly could mean winding up on an unmarked barge headed far offshore.

Gangs And Factions

Locke’s Quay Constabulary – Numerous but disorganized. Their main goal is to keep customs running smoothly, not to enforce the law.

The Navy – Present but not omnipresent. They exert influence through bureaucracy and intimidation.

Ironhatch – Assassins with access to body disposal via junk barges. Efficient and terrifying.

Naval Gazers – Smugglers who operate out of the shipyards. Known for modifying vessels and running contraband.

Sibs of Siren – Tattoo artists, gossips, and assassins. They run Sirens’ Landing and trade in secrets as much as ink.

South Rocaphen (aka Rocaphen)

South Rocaphen is a district born from exhaustion — a suburb that grew out of the city’s mining operations. As the mines were depleted, the district expanded into the hollowed-out spaces, creating a layered, sunken sprawl of stone, steel, and soot. It is a place of industry and resilience, where the ground itself has been carved into homes, workshops, and strongholds. The air is thick with dust and the scent of labor, and the people here are tough, proud, and fiercely territorial.

Landmarks

Cordwain’s Own Bastion — A fortified district outpost for South Rocaphen’s Constabulary, where officers operate with precision, balancing their role between industrial oversight and keeping gang conflicts from escalating too far.

Quarry Row — The heart of Second Rocaphen, where homes have been carved into the old stone pits. A maze of reclaimed tunnels, makeshift workshops, and hidden gathering spaces, fiercely defended by the Underminers.

Sledgecross Yard — A training ground for the Bricklayers Union, where members test the strength of their tools, reinforce structures, and handle disputes in their own brutal, practical fashion.

The Cutwell Den — An underground market hidden within a collapsed quarry, where smuggled goods and unregistered mining tools are exchanged. Flintbacks control access, ensuring only trusted hands make deals here.

The Emberlock Square — The district’s central plaza, once a wellspring for water traders but now the main gathering point for workers and business leaders. Wellhawks patrol it vigilantly, ensuring safety in the otherwise tumultuous cityscape.

The Gearsward — A sprawling rail interchange where mining carts are loaded onto larger trains for transport down the mountain. Flintbacks operate discreetly here, sneaking contraband among legitimate shipments. It’s also the great engine that drives the gear stations around the district.

The Stillglass Foundry — A massive glassworks where industrial-strength panes, lenses, and bottles are crafted. The furnace glow never fades, and Wellhawks keep its perimeter secured from reckless thieves.

Trestlecrown — A towering steel bridge built to support Rocaphen’s trains as they descend toward the city below. It’s both a breathtaking landmark and a critical transport artery, closely monitored by the Constabulary.

Gangs And Factions

South Rocaphen Constabulary – A powerful force outside the tunnels, thanks to reinforced chokepoints and control over mining roads.

Wellhawks – Water hawkers with access to the district’s supply. They also act as a semi-official security force.

Bricklayers Union – A labor union with muscle. They train, build, and settle disputes with practical brutality.

Flintbacks – Miners turned smugglers and fraudsters. They coordinate theft and contraband across multiple sites.

Underminers – Guardians of the lower tiers. They provide protection and enforce order in the sunken parts of the district.

St Biscuiton’s Provided (aka The Cannery)

The Cannery is not so much a district as it is a sprawling industrial organism — a tangle of businesses, factories, and processing plants that grew out of a single enterprise and never stopped expanding. It famously lacks a police station, relying instead on private enforcers and corporate muscle. The Cannery is loud, hot, and dangerous, with a rhythm all its own. It’s where labor meets exploitation, and where the smell of whale oil never quite fades.

Landmarks

Briggen Slaughterhouse — A specialised service for the slaughter of almost anything that comes out of the sea. Most of its bulging warehouse space is dedicated to the foul task of dismantling the strange and alien whales of the Gyre, but they also have the infamous P&P boiler, used for P&P Oil.

Gripp and Pipe’s Union Of Gripp and Pipe — Rather than a police station the Cannery has Grippe and Pipe, a business of strikebreakers, counterorganisers and indigent corallers. Grippe & Pipe are funny cartoon mascots for the people they represent.

Moist Lane — A slop discharge lane for multiple parts of the cannery. The worst houses flank it, atop a towering wall, and the street runs over audibly active gross fluids. It smells ferocious. Famously cop-light.

Pippin’s Paytower — A single large tower that exchanges company scrip for actual coin, the Paytower is a famously robust one-stop shop for Cannery workers to get paid, so St Biscuitons doesn’t need to transport money to many locations. Fights are common.

Gangs And Factions

Gripp & Pipe Labor Negotiators – Not a gang in the traditional sense, but a powerful force. They operate on their own schedule and enforce corporate interests.

Yard Rags – A loose mob of bravos, traders, and opportunists. They’ll do anything for a bit of extra cash.

Rib-Crackers – A lightly corrupt crew that operates like a union — but isn’t one, because if it were, Gripp & Pipe would crush it.

Pit Kickers – A hardened gang that deals in raw whale blood. They’re tough, dangerous, and deeply embedded in the Cannery’s economy.

River Pigs – Hitters who specialize in body disposal. If someone disappears in the Cannery, the River Pigs probably helped.

The Chantry

The Chantry is the spiritual and cultural heart of Gyre’s Church — a district of towering cathedrals, sacred gardens, and quiet surveillance. It is a place of worship, education, and judgment, where class divides are etched into the very pews. The Chantry is both sanctuary and stage, where sermons are delivered, secrets are kept, and power is sanctified. It is beautiful, solemn, and always watching.

Landmarks

The Basilica of the Three Gates — A towering cathedral of white stone and stained glass, this is the spiritual heart of the Church. Its three massive doors — each representing one of the Gates — are only opened on high holy days. The wealthy worship in the gilded upper tiers, while the poor gather in the shadowed nave below. The Medicants maintain a quiet presence here, watching.

The Chapel of the Quiet Flame — A small, elegant chapel by the riverside, known for its silent services and candlelit rituals. It’s a favorite of the upper class, who come here to confess without being heard. It’s a place where upper and upper-middle classes can actually interact, albeit through passed notes.

The Cloister of Saint Arthruongus — A serene, walled garden and seminary where the Church trains its future clergy. The fruit trees here are older, twisted, and carefully pruned. Students chant in the mornings and debate theology in the afternoons.

The Ember Court — A public square where sermons, trials, and – back when such things were common enough – church executions are held. The ground is scorched from past burnings, though it’s been paved over with white stone. The Medicants do public lessons on ‘spiritual hygiene’ here.

The Fruit of Grace Walk — A long, tree-lined promenade that winds through the district, connecting seminaries, shrines, and schools. The fruit trees here are bloom year-round and nobody knows why (but it’s probably shifty). It’s a place of peace, but also of quiet surveillance — Chantry police patrol it in pairs, always watching.

The Hall of Ash — A long, open-air colonnade where the Medicants display the remnants of their purges — burned charms, shattered tincture bottles, and scorched effigies. It’s both a warning and a sermon. There are even large, human-sized bird cages that have not been used since the Emancipation suspended on high columns – which means the human bones in them are bleached quite white.

The Lantern Archive — A vast, multi-tiered library of religious texts, folk records, and banned writings. You need signed permission to come here, but it is an invaluable archive.

The New Politano — A large, religious eatery, a place people go after church to contemplate and communicate and also, a corrupt business where Bridge Grunts do deals and make trades. Disturbing the peace is one of the only offenses a made member can do that remove their protections.

The Open Tithe — The Church’s bank, housed in a fortress-like building of pale marble and ironwood. Ostensibly, this is the place people can go to donate to the church, but also, look at the church’s books to see where money is being spent. The Candlekeepers have a strong presence here, ensuring their wares are always in demand. The Bridge Grunts have tried to skim from it — once.

The Reliquary of Saint Morrow — A museum-like vault of sacred relics, including bones, robes, and “miraculous” artifacts. It’s heavily guarded and open only to the devout — or the wealthy. Most notable, though, this is one of the centers of Kings Resort information brokers.

Gangs And Factions

Bridge Grunts – Control the bridges between the Chantry and Wickstand. They operate on a contract system and enforce movement rights.

Candlekeepers – Providers of liturgical goods made in Gyre. They ensure the Church’s rituals are well-stocked and well-paid.